Once exclusive to those with access and money, photography is now in the hands of anybody with a phone. To communicate today is to know how to Instagram your meal in the right light or how to picture yourself in the right pose. Literacy in the language of photography fast approaches a necessary education. Nearly everywhere you go an ever-present camera may do what it pleases with your image. Has there ever been a time when knowing how your image is viewed has mattered so much?

Yet a flood of images—from memory, from painting, from poetry—has always been with us. What hasn’t been witnessed before is an availability of image-seizing tools. The freedom to shoot is now everybody’s. Perhaps in response to this flood of picture-making, some photographers, including a stable featured this past May at the J. Paul Getty Museum, in Los Angeles, have stepped back to older tools with a forward thrust. Labeled by the New Yorker as “photo-materialists,” they’ve taken an older language to direct contemporary eyes to what’s still possible in the frame.

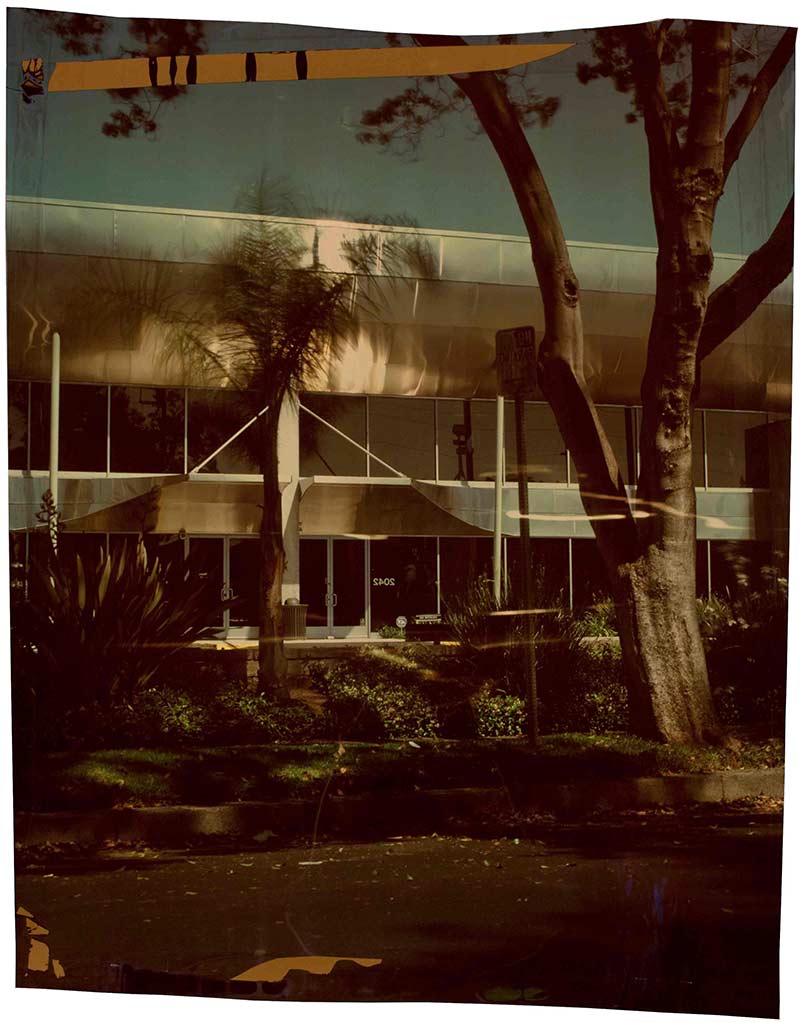

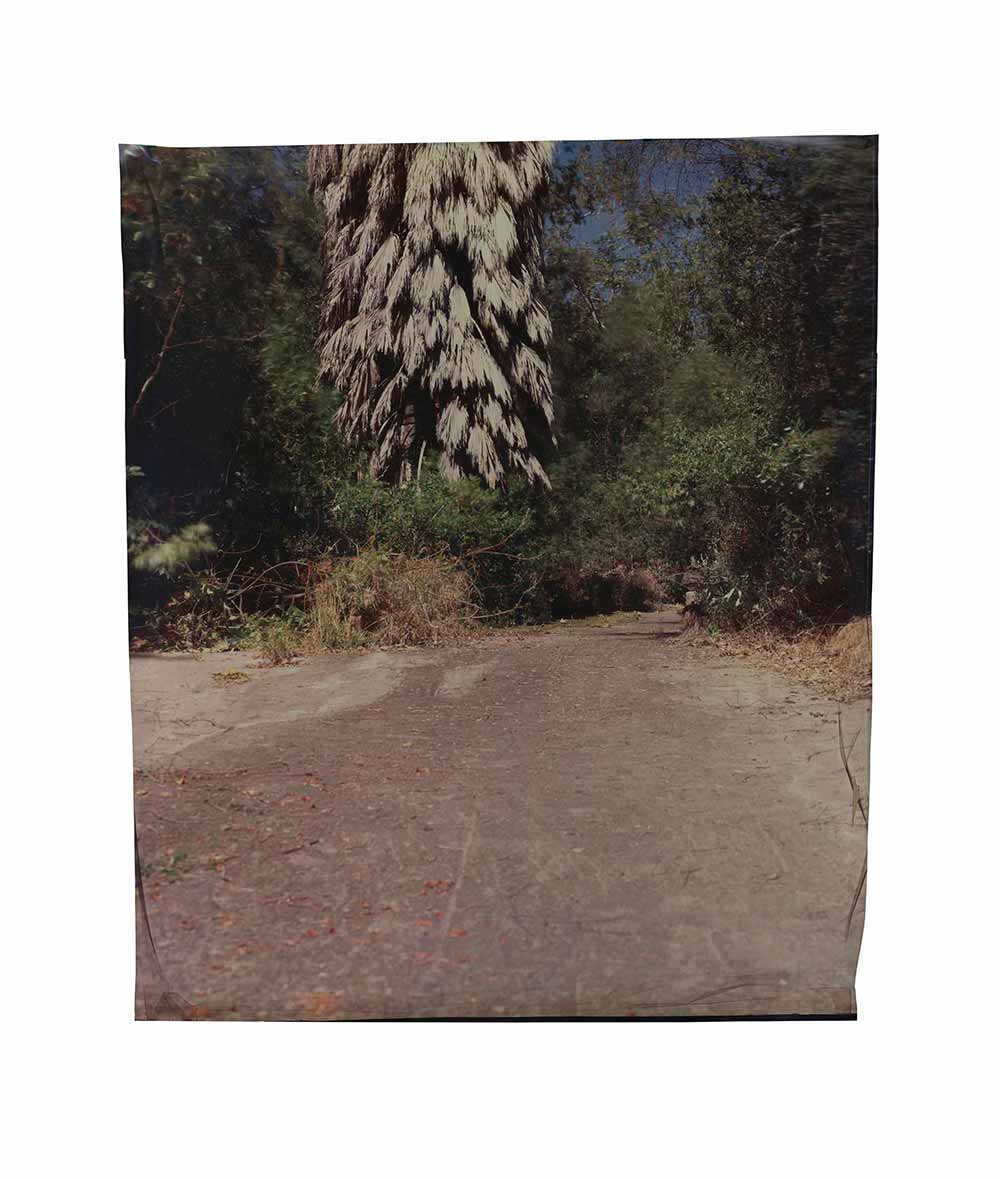

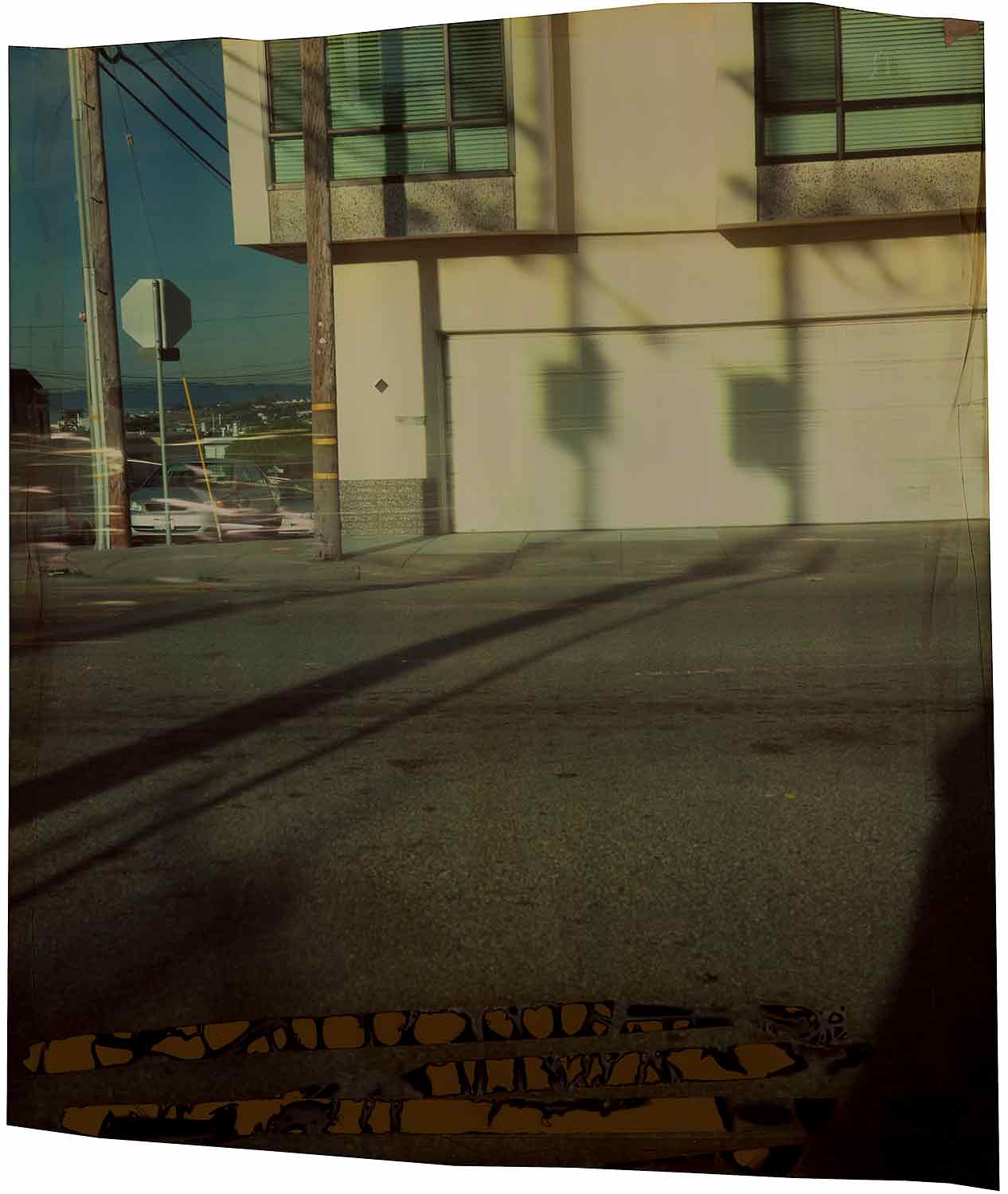

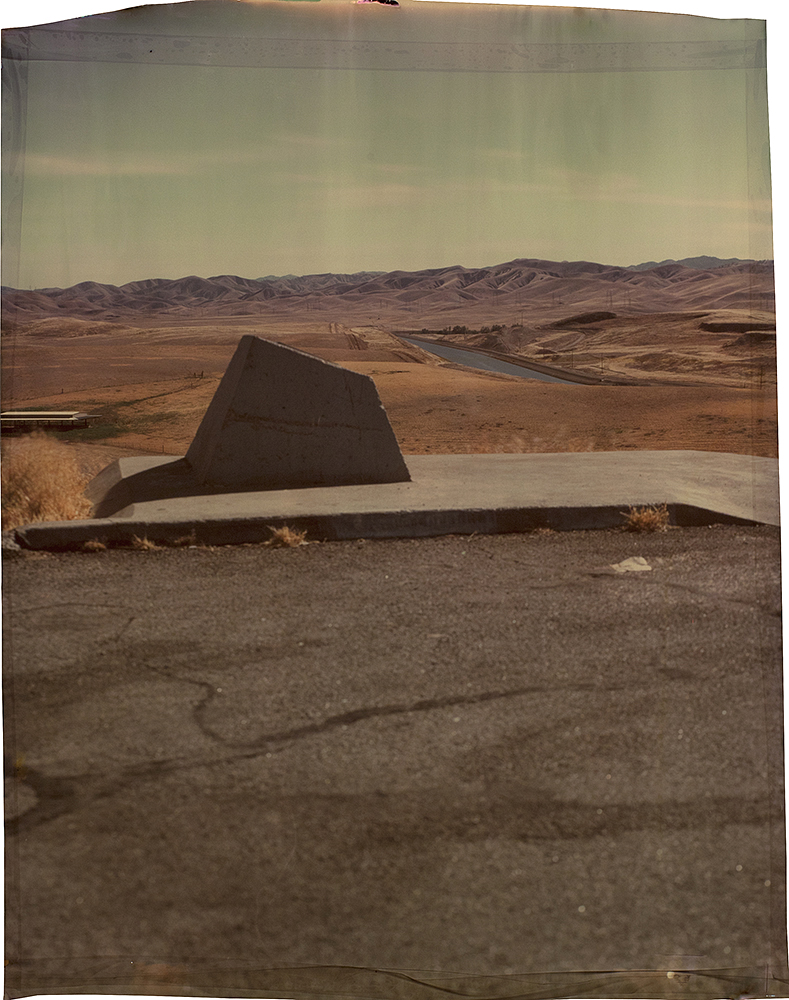

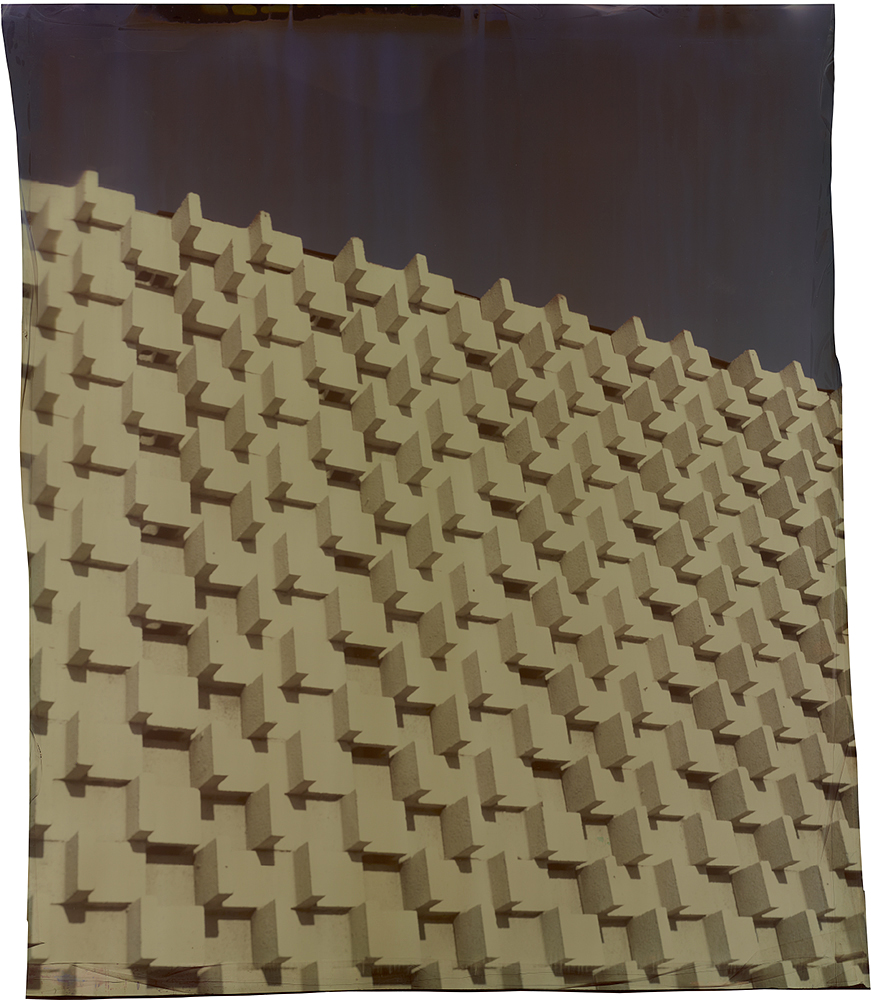

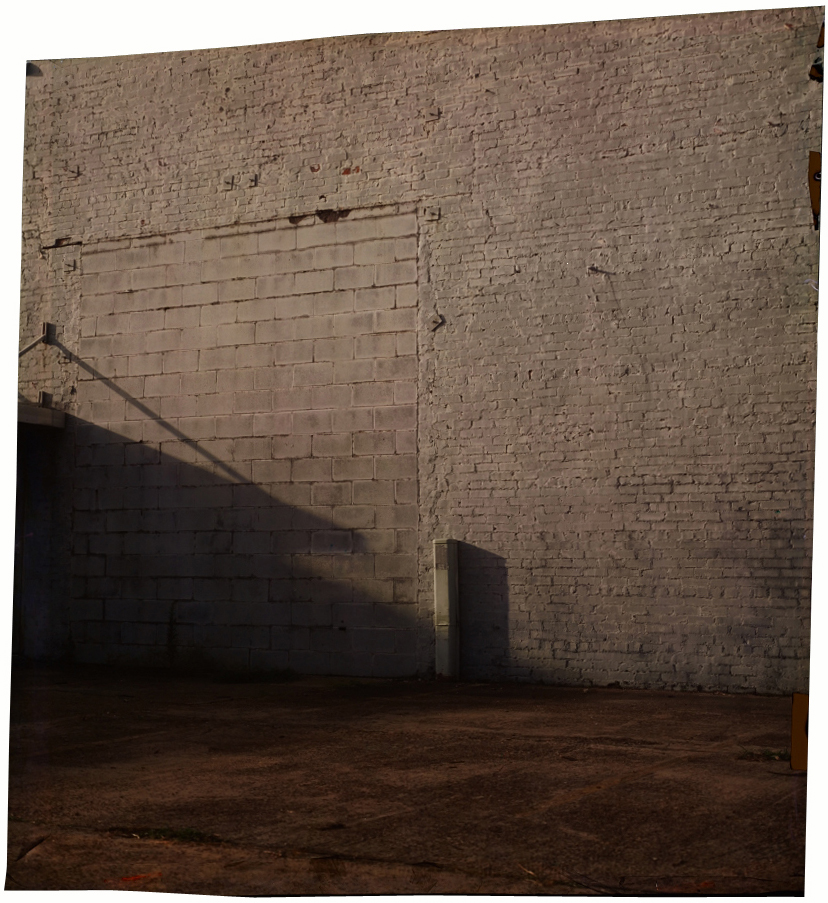

Some like John Chiara have gone back to the very beginning and reclaimed the camera obscura. On the streets of San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Coahoma, Mississippi, he drives around with one as big as a small shed. In this retro-wormhole of a camera, a new view can be revitalized with an old physicality. Chiara’s images are objects. In his language, those objects can then become pictures of memory and space. “I feel photography has a long and complicated relationship with memory and the madness of the self-encounter,” he says. Mystery, a purposely darkened insight, is part of his process, and so is chance and intuition. But it can all be as simple as doing what has always been done, too. “People approach me all the time when I am out shooting and ask what I’m doing. I answer simply: this is a large camera and I am taking a color photograph.”

I spoke to Chiara over email about his work and his experimental photography techniques.

Your first camera was a Nikon given to you by your father. You’ve mentioned being seduced by photography at very young age. What seduced you? How did you get your start shooting?

I was incredibly aware of how I was looked at and perceived as a child. I found photography to be a powerful tool to develop my own sense of how to look at the world around me. I think I was drawn to it because it was fun and felt empowering.

In 1980, I received a Nikon F3 and several rolls of color film as a Christmas present. The F3 was introduced that year with aperture priority automation – the camera would select the correct shutter speed for exposure control. A sophisticated piece of equipment for a 9 year old, and a real luxury for our family. My father was very excited and showed me how to load the film and other camera basics. I went outside and shot all the rolls in an hour or so. When the results came back from the lab, my access to film was severely rationed for several years.

If a stranger were to ask you to describe your work while you were shooting, how would you describe it?

People approach me all the time when I am out shooting and ask what I’m doing. I answer simply: this is a large camera and I am taking a color photograph. They often ask if it is a pinhole camera and I say no, and point to the precision barrel lens on the front of it. They ask about the size, and I explain that the picture format reflects the camera size. I enjoy these interactions, but I never stop working to talk.

You’re described as a “photo-materialist,” a photographer, as the New Yorker put it, who works with the “bare essentials of paper, chemicals, and light” to create photographs. How does the word photo-materialist sound to you?

The term feels like a bit of a stretch, but I understand the desire to put a name to things. I have mixed feelings about the beginning premise of the New Yorker piece: “At a moment when smartphone users send more than a billion digital images cloudward each day, a growing number of contemporary artists are turning away from screen-based images to explore the photograph’s existence as an insistently material object.” It may be true that there is a trend in contemporary art in which artists choose to work with the photographic medium or use photographic materials to make works of art. But to say that some artists are turning away from screen-based images is neither here nor there.

The overwhelming trend in contemporary art, art education, and museum programing for several decades now has been to foster interdisciplinary practices that incorporate working with new media as a component of artistic expression / genius. Thus, it has become easier than ever to digitally output a photograph of exhibition quality. Screen-based images are everywhere and nowhere at the same time, as media projections that we consume, use, edit and broadcast.

As it appears, “new photo-materialists” is a term coined to describe art historians employing methods for contextualizing the history of photography by considering photography according to its material conditions of use and the networks created by those conditions. As Owen Clayton writes in Literature and Photography in Transition, 1850-1915, this approach “avoids questions of representation all together.” It is used in the New Yorker piece you refer to (“Experiments in Analog Photography,” Christopher Phillips, The New Yorker): to describe the artists who are “dispensing with the camera and lens entirely” to “employ the bare essentials of paper, chemicals, and light to fashion near-abstract images that have a tantalizing physical presence.”

I do not think the term was cast at me directly or suitably describes my process or intention. Nor does “fashion near-abstract images” apply to my work. I am particularly invested in using my cameras and my lens. I take photographs from the inside of a camera obscura. Timing the exposure as one does in a darkroom, while augmenting its projection onto a large sheet of photographic paper.

Although, similar to the “photo-materialists” school of thought—I understand photographs to be equally images and objects. The materiality of a photograph plays a part in its meaning, not alienated from or secondary to what can be gleaned from an image alone. For instance, when people look at my images online they might read them very differently than if they saw them in person. The physicality and reflective nature of the photograph doesn’t translate online.

In working with a camera that shields you from its final result, you’ve said that you might have, in effect, forced yourself to rely on intuition. What does intuition mean to you, exactly? How does it guide your work?

I think I learn from each photograph I take. I only take a few on any given day. The setup and act of taking the photograph is a slow process, and it is often a while before I develop them. This gives me ample time to think about what I did, and I take careful notes for each exposure. After I develop the pictures, I consider my notes and recollect while studying the results. This process develops my intuition and and my sense for photography. It is one of the main forces in the direction of my work. It frames the window my curiosities can peer through.

I’m interested in knowing how you think your work depicts memory. You say your photographs aren’t nostalgic. Could you explain that idea more fully? If nostalgia is longing for the past, what are your photographs revealing about how we think about the past?

I personally am not interested in nostalgia. I had an interesting childhood, but I do not carry happy, sentimental or wistful affections for the past. I do not long for it. I am interested in how memory is recalled. When working in a particular area, I consider its identity and the photographic collective memory that enlivens the landscape and gives it a sense of place.

I have been approached by people at receptions to be asked where the work was made, because the photographs recalled memory of their past. One person thought the photographs were from Columbia, where he grew up. A curator once discussed how one picture of a street scene in San Francisco recalled memory from her childhood. The perspective was from the sidewalk with the lens around 3 feet off the ground. In the foreground there were large brown marks where I purposely left 3 strips of tape on throughout the development, which obstructs the image (below).

I feel photography has a long and complicated relationship with memory and the madness of the self-encounter. I find that moments of reconciliation produce strong visual memories. As time passes, the subjects of reconciliation fade away, but their psychological weight has burned the visual into memory.

Visual memory seems to always be in flux. Memories are unbound, with divergent edges. You have to move around in memories to get to points of clarity.Through Photography I’ve tried to set up a physical process that has parallels a psychological process.

I also read that you pre-visualize your photographs. I imagine daydreaming while walking around a city plays a role. Does it? What does pre-visualization involve? When do you know you’ve found something to shoot?

Pre-visualization develops through practice, knowledge and experience. It is a process of refining one’s intuition and photographic sense to recognize the potential photographic opportunities immediately about. This is why I’m always taking notes: to train my eye to find these moments of clarity.

You mention that you welcome imperfections in your work and accept noise as part of the process. But you’ve also said that any damage or erosion that happens to your photograph, after you’re finished processing it, harms its integrity. I’m wondering whether there is a difference, considering that your work explores the physical boundaries of a photo. What do you think? What’s the distinction between damage and imperfection, when in time any preservation will prove to be imperfect?

I photograph directly onto photographic paper inside oversized cameras because I want to record the tactility of a camera obscura image and hopefully qualities of its ephemeral nature. I primarily use Ilfochrome Super Gloss Ultra Deluxe paper because of the qualities of the material: its color range, saturation, reflective nature (physicality) and most of all because it is by far the most archival color photographic paper ever produced.

I don’t think I welcome imperfections. I think of my process as part photography and part event. I welcome aspects of the photographic event to be recorded wherein the result has a multiplicity of image, object and document.

Where do you want to shoot next? Have you shot in Texas? Highway 67 between Marfa and Alpine is really beautiful. You might like it.

Right now I am shooting in Mississippi, Manhattan and the Hudson River Valley.

All images © John Chiara. See his experimental photography techniques here.

Home » John Chiara Interview: Photography in the Internet Age, Looking Back to See Ahead

John Chiara Interview: Photography in the Internet Age, Looking Back to See Ahead

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

Get our latest deals, freebies, exclusive offers & get 10% off

More Articles Like This

Nikki Brown Interviewed : Professional Life, Boudoir Shoot Tips & More

April 8, 2024

Nikki Brown is a professional boudoir photographer. Her portfolio highlights her skills in various types of photography, including boudoir, swimsuit,

Best Mother’s Day Photoshoot Ideas That You Must Try

April 4, 2024

Are you looking for the perfect way to celebrate the day that the extraordinary woman who has given birth to

How Big Is a 4×6 Photo – In Pixels, mm, cm & Inches

March 29, 2024

4×6 is the most commonly used and standard photo size as it mirrors the aspect ratio of the viewfinder of

Nikki Brown Interviewed : Professional Life, Boudoir Shoot Tips & More

April 8, 2024

Nikki Brown is a professional boudoir photographer. Her portfolio highlights her skills in various types of photography, including boudoir, swimsuit,…

Read more >>

Kimber Greenwood Interview : Unmasking The Creativity Of An Underwater Photographer

February 2, 2024

Have you ever wondered what it takes to be an underwater photographer? How do they capture the amazing scenes in…

Read more >>

Sarel Jansen Interviewed: All About Commercial Photography

February 1, 2024

Sarel is a renowned commercial photographer based in London. He has worked and shot amazing photographs for small and large…

Read more >>