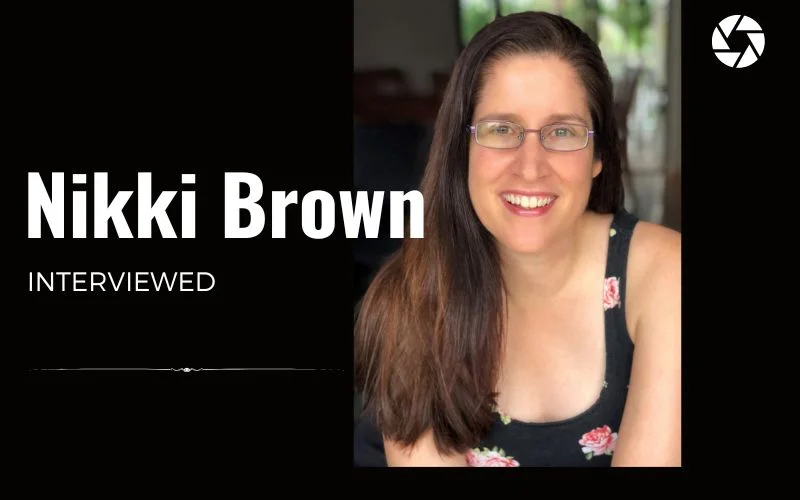

Meet the Writer, Photographer and Journalist in Brad Zellar

“You will see things that no one ever looks at or sees closely . . . ”

In Catch and Release: My Photographic Journey, writer, photographer and journalist Brad Zellar writes about a man who, realizing he’ll never capture a photograph as beautiful as what he sees around him, digs a hole, purposely beside his two dead dogs, and buries every single photography equipment he had ever owned, burying them along with the entire promise photography had for him. Caught with the empathy to see, this man releases his desire to capture. He abandons all that he loves simply for loving it too much.

“I look at photographs and hear voices,” was the Zellar quote that led me to this story. It was a tweet for a short interview from the Paris Review. I read it in a frenzy. And when I got home, I read as much as I could about Zellar. Soon, I realized (though before sending the questions) that Catch and Release was about him.

Zellar actually did quit believing that he could become a photographer — actually got rid of his equipment, too. Yet unlike the man in that story who never expands beyond his hometown library, Zellar is now one of the best writer, photographer in the world.

I assume, at this point, you’re probably wondering why you should care? Or even thinking about why it all matters? How can some journalist from Minneapolis, Minnesota teach you anything about making better photographs? If you’ve never wanted to understand why you were pulled into shooting what you shoot — or wanted to know why, suddenly, and overwhelmingly, photography became not just something you do but something you are — then you’re right.

Brad Zellar ain’t your guy. But if these questions have ever entered your mind, then you’ll appreciate someone so photography obsessed like Zellar.

Because, like him, you love photography, it expresses — communicates — who you are more than anything else in the world. While other people were focused on watching reality TV, or lounging around, or drinking, you stuck your nose behind that beautiful camera body and shot.

Shot again. Shot until gradually, quietly, an identity emerged. And these are the voices Brad Zellar hears in the photos he sees. These sparkling whispers of identity communicate the photographer you are. And because of Zellar, I was sent toward learning what I was looking for, and I knew that if this happened to me, I needed to share him with you.

In this interview, Zellar critiques his own photography, explains why every picture has the power to recall lost worlds, and reveals what makes a photograph successful.

The closer I read your thoughts on photography, the more I wanted to ask the big questions. So, here, at the very beginning, I’ll ask the biggest ones. What makes a photograph successful? What makes a photograph beautiful?

The beautiful part is, I think, purely subjective, but a successful photo to me is a picture that presents a mystery or poses a question, or questions; there’s something going on there that fascinates and draws you in and makes you want to come back to it again and again. Sometimes the question is nothing more than the question you pose: What makes this photograph so interesting to me? Other times –and this is true of many of the photographs I love best– the question is as simple (and huge) as this: “Isn’t this a world of wonders?”

Your work with Alec Soth reminds me of a quote from Gabriel Garcia Marquez: “Reportage is the complete story, the complete reconstruction of an event. Every little detail counts. This is the basis of the credibility and the strength of a story.” Do you think photography could replace the first and last word in that quote? Are the LBM Dispatches reportages in Marquez’s sense?

I don’t think anything can truly be the complete story, and I’m not sure that what Alec and I have been doing with the LBM Dispatches can be considered reportage in any sort of a purist sense. Because we’re always moving through these places, our encounters tend to be hit-and-run; they’re snippets, really, of the bigger stories and histories of the people and places we visit. I do, though, believe that allowing the pictures to speak a little bit takes away some of the mysteries that real reportage is supposed to address –the who, what, where, and when sorts of questions– but in some instances those same answers can also raise further questions, and help to build a kind of narrative. We shape that narrative, though, so there’s always a form of manipulation going on.

When starting to write about a photograph, you say that you “make forensic inventories of every piece of information . . . and [create] a list of questions the photo poses”. For this particular photograph, what would those questions be? What detail would you say communicates the most?

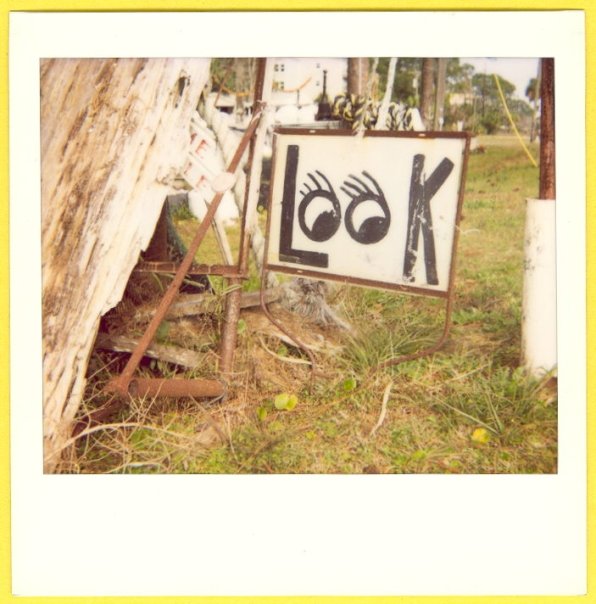

That forensic business isn’t quite as interesting or important to me with photographs that I’ve taken. For me, when I’m traveling, photos serve as a form of visual note-taking or record-keeping. I have an assortment of Polaroid cameras, and that instant form is perfect for the way I work. But I was there, pointing a camera at this billboard somewhere in the Mississippi Delta.

I suppose I was interested in it because like so much else down there it is a relic, something that’s been standing in the same place for a very long time, and which now means something very different than it might once have meant. I don’t think it’s selling anything anymore; and it’s shot full of holes. I can look at it now and recall that day, the stillness and aquatic light of that desolate road (I was looking for the grave of a dead blues musician), and it somehow captures the mood of that entire trip.

You’ve written that your father said: “A great photographer can find desolation in even the brightest colors, romance in squalor, heartbreak and loneliness amid jubilation, and beauty in even the most ordinary objects–maybe beauty is not even the correct word. Grace, that’s perhaps more accurate.” Could you explain what grace means? What would you say makes a photographer great?

I should explain that that particular piece of writing –’My Photographic Education’– is a fiction, and I suppose the father is standing in for me. His thoughts and frustrations with photography are pretty close to my own.

I also was once whole hog about taking pictures and had lots of gear, but at a certain point I realized I wasn’t very good at it and got rid of everything. What I liked was photographs; my own pictures were of things I’d experienced and seen in a certain way; I didn’t feel like I could capture that, and as a result they didn’t seem as successful or interesting to me.

It was at that point that I started really collecting photo books. Anyway, I guess grace to me is the ability to stand outside yourself and see the world clearly even while you’re immersed in it. It’s navigation, fundamentally, moving through things and situations with curiosity and care. As far as what makes a photographer great, I think I approach that question as a writer: there’s that corny old notion that a picture is worth a thousand words, and I love when I feel like a photo really does stand that test, when I can recognize that it would take me at least a thousand words –and sometimes many, many more– to get to the bottom of it.

I’d like to discuss two of your photographs (the first in the interview and the one above). For each one, could you explain what questions these photos pose and tell us whether you think the photograph was successful? What were you looking for in each?

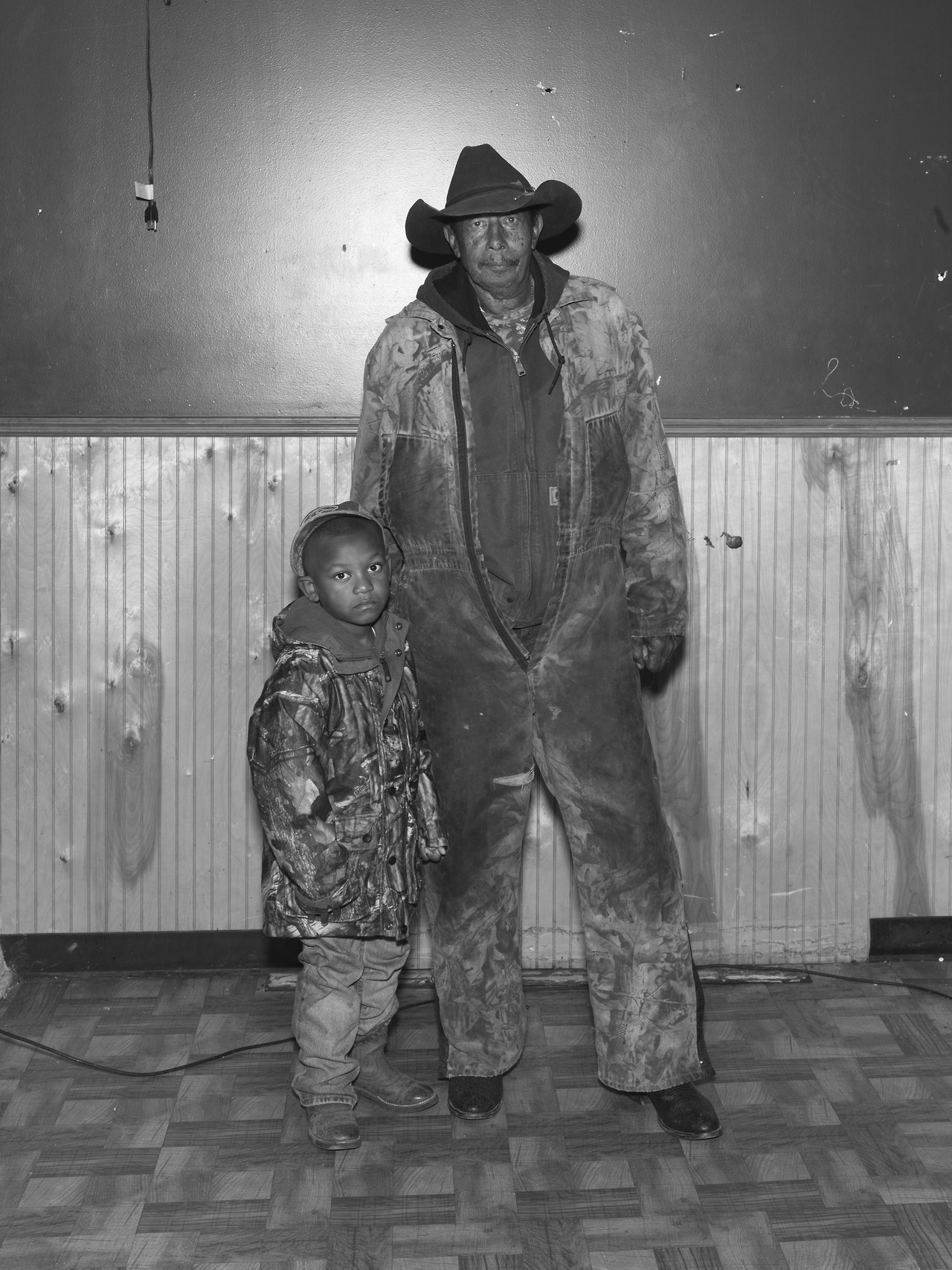

Again, I wasn’t really looking for a photo in either of these situations; I was taking notes. My own photos are successful to me to the extent that I can look at them and remember where I was and why I took them. I don’t think that’s the standard of a real photographer. The first of these photos was taken at a Moose Lodge in Clyde, Ohio, on a Dispatch trip.

We spent an entire day and night at this place, had an incredible time, and I ended up joining this particular Lodge (Long story, but I lost a tabletop shuffleboard bet). What I loved about that place was the same thing that attracted me to the billboard in Mississippi: the sense that there are still places in America where things change very, very slowly.

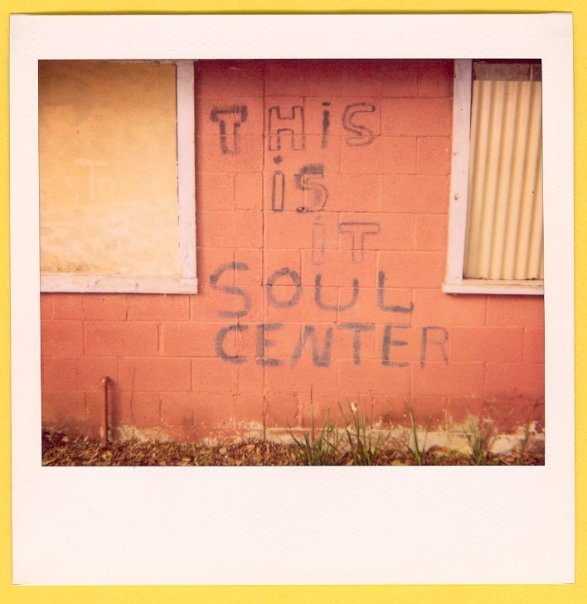

The Moose Lodge in Clyde was like a perfectly-preserved diorama from my own childhood in a small town in Minnesota. The other picture is from the Florida Panhandle. A few days before I stumbled across this roadside memorial I had read in the local paper about a fatal car accident involving a young woman. Like most such newspaper accounts, it was very brief; there was no sense of what had happened other than that someone had been killed.

Seeing the memorial there along the road, right next to the Gulf of Mexico, gave the whole thing a more tragic and human dimension. Too many photographers, of course, are attracted to these roadside memorials, but there’s something undeniably touching, and even haunting, about them. If you stop and poke around, and check out the notes and other things people leave there, they become sort of visual obituaries.

You’ve written that, “the most painful sort of nostalgia is for something that is not yet gone”. I think this sentence could also explain something about photography, about how it immortalizes objects that have yet to pass. What would you say?

I agree with that. I believe that. I think the etymology of the word nostalgia is “the pain of returning home,” or something pretty close to that. If you live long enough you start to have an understanding of how tenuous pretty much everything is. Once you start losing people and things you love at a pretty alarming clip, it’s harder to ignore the sputtering hourglass in the back of your skull. Every picture is essentially a picture of a lost world, but in the same way every picture has all the power of Proust’s famous madeleine, the bittersweet ability to recall lost time in the most brutal and beautiful and aching ways.

“Carry a tune. Carry it with you until it’s capable of making you and those dear to you dance.” This is the last advice a character of yours says in his last note. I think it’s a good illustration about finding someone who understands you. I got to thinking, is that what all art amounts to in the end? Finding someone who appreciates the same tune?

Exactly. That’s what it’s all about to me. Make music, sing harmony, find your band, and dance whenever the urge moves you.

Be sure to check out the work of this writer, photographer and journalist on his blog and at Little Brown Mushroom.